Malpaso (2019) directed by Héctor Valdez

Malpaso (2019) directed by Héctor Valdez

Program Notes by María Elena de las Carreras

September 4, 2023

The Nueva Onda and Nepantla sections of the Latin American Cinemateca showcase the works of emerging and experimental directors, worth gaining critical attention beyond their countries and the specialized festival circuit. It may not be an easy task for programmer Guido Segal to find pearls for the Cinemateca screenings, but the quality of the films presented is a reward by itself. Mexican filmmaker Andrés Kaiser’s Feral (2018), shown in 2021, was a self-assured exploration of psychological horror and the documentary style. Como el cielo después de llover (2020), screened earlier this year, was the debut film of Colombian director Mercedes Gaviria Jaramillo, a remarkable first-person autobiographical documentary about the art and craft of filmmaking.

It's now the turn of Malpaso, the first feature of Héctor Valdez, a director and producer from the Dominican Republic, a country well set up for location shooting of big budget productions requiring exotic locales. Valdez, who graduated from McGill University in Canada and returned to his country to work in film, has been active since the 2010s, directing and producing movies for television and documentaries. This training serves him well in Malpaso, the work of a filmmaker trusting his talents and gathering a top notch team of collaborators.

“Malpaso” is the name of a small town located in the Dominican Republic border with Haiti, on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean. In Spanish, it means “bad step”, physical or metaphorical, ominous denotations that the film subtly absorbs as the story develops.

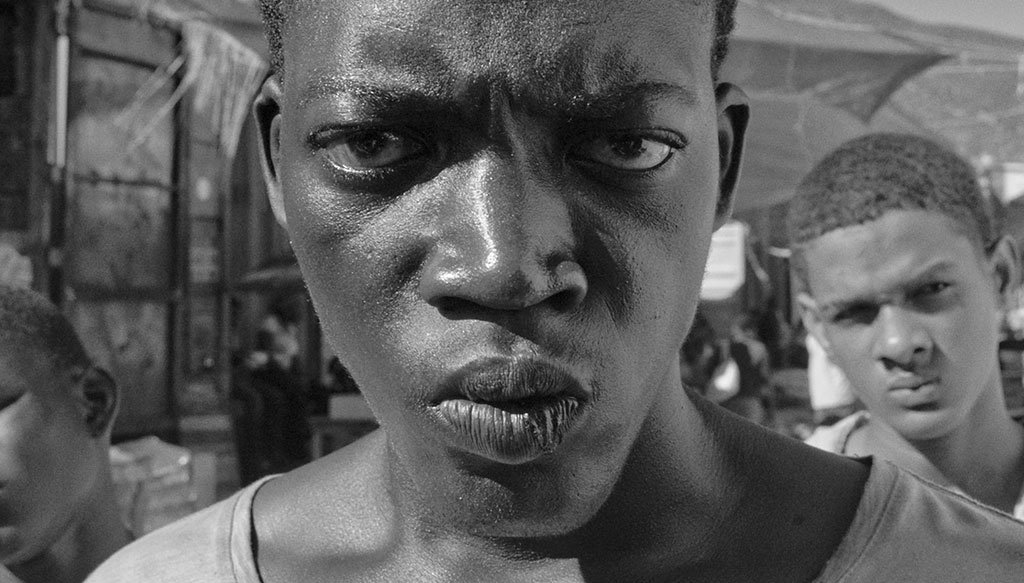

Based on a story by Valdez, with four writers listed in the credits and exquisitely shot in black and white by Juan Carlos Gómez, Malpaso follows twin brothers, Cándido (Ariel Díaz), who is albino, and Braulio (Luis Bryan Mesa), very black. Their birth in a desolate rural shack, seen from the point of view of their black grandfather who brings them up, is s shocking yet restrained set up for the plot: the whiteness of Cándido is a disruptive factor – truly a bad omen - when, orphans at 15, the boys need to survive in near Malpaso, selling their only possession, a donkey.

The first words of the film explain the whiteness/blackness purely in magical realist terms. The black twin – from whose point of view the story is told in a flashback – says: “This is the story of how we were born. You are white as the moon, and I am black as the night. Once upon a time there was a man who fell in love with the moon but he was also in love with the night”. So, at one level this dichotomy works by complementing, not opposing, the black and the white; but at a more pedestrian level, the albino’s whiteness and his strange facial features scare the black people of Malpaso, with the exception of an Haitian old healer who believes in curses and zombies. The “different”, “the other” will find no place in Malpaso.

In his portrait of a small rural town, overtaken by a petty crime lord, La Cherna (Pepe Sierra) dictating its social and business dynamics, Valdez imaginatively reworks the tropes of Cinema Novo – the Brazilian innovative response to Neorealism and New Wave in the 1960s: black and white cinematography, non-professional actors, a searing portrait of poverty and despair. The film lands also in the brutal territory of urban violence and squalor later captured by Pixote (Hector Babenco, 1980) and City of God (2002, Fernando Meirelles), but it does so astutely observing the dynamics of exploitation and misery in a smaller scale.

The creative voices of Valdez and collaborators, however, go beyond these Latin American models to locate the film in a place that is both poetic and realistic, drained of fast-paced action, and understated as well as moving in its emotional impact. Nothing is on your face in Malpaso, so the unimaginable future of the albino twin, when his brother is no longer there to protect him, is fully rendered by the cinematography and the evocative music of Pascal Gaigne. It’s a fantastic use of two film techniques approached with restraint. The film may keep the story cryptic and elusive, but the full extent of the horror, the horror, and the resilience of the fraternal bond are made explicit by a confident use of cinematographic language.

Malpaso may not target a large audience looking for thrills. But as an impressionistic and tender portrait of two barely literate brothers separated by social and economic circumstances outside of their control, understood by all but not explained or denounced, is worth a dedicated viewing. This beautiful film may be short on action and dialogue but packs an emotional punch. The ending leads to a catharsis that Aristotle would have been pleased to recognize as the true function of tragedy.